INVESTIGATING HISTORY SERIES:

September 3 and the End of WWII in the Philippines

THE LAST DAYS OF THE JAPANESE KEMBU COMPOSITE DIVISION IN ZAMBALES-PINATUBO AREA – 1945

THE WAR ENDS

September 3, 1945 marked an important milestone in the History of WWII, the official surrender of all Japanese forces in the Philippines with the outcome of the ceremony for the signing of the capitulation by General Tomoyuki Yamashita in Baguio. The date precedes of the September 2, 1944 on the surrender ceremony of the Japanese on the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. Now going back to our own backyard, in the shadow of Mt. Pinatubo, where the Bamban-Zambales mountain range became the main basement of the Kembu Composite Division (Kembu Group) of more than 30,000 men, mostly army, navy, and airborne paratroops for the defense of Clark Field. Although, this figure was considered by the official US Army records, there are several references, mostly Japanese sources (report of Captain Sadao Hachisu of the Takayama Shitai and Lt. Shinjo Akamatsu of the 17th Naval Combat Sector; all from Kembu Shudan) that put the figures between 40,000 to 55,000 strengths.

At the war ends, the nearest number as to the survivors of the Kembu Shudan was at 1,500; an almost complete destruction of the composite division. Aside from the battle casualties, the lack of food and medicine, the impact of rainy season to the sickly, wounded, and hungry troops. Most of the high-ranking officers and field commanders of the Japanese Kembu Group in Bamban-Clark area were killed, including Vice-Admirals Kondo and Sugimoto, Colonels Takayama and Miyamoto, making the former battlefields their open graves and buried tombs for those who died or committed suicide inside the many tunnels typical in the Bamban and Zambales mountain.

THE ROLE OF FILIPINO AND AYTA NEGRITO GUERRILLAS

The role of the Filipino guerrillas including the Ayta Negrito mountain patrol were far from being recognized in the annals of the combat operations against the Japanese Kembu Group in the Clark-Stotsenburg-Bamban area of Central Luzon. Perhaps few citations can be found in some published books, if any, or that US Army military records like the combat journal (which we have some, from the US National Archives at Bamban Museum) of 40th Division. In an attempt to get a wider view of the role of the Filipino local guerrillas and the Ayta Negrito mountain patrol forces who participated in the ground offensives on Japanese Kembu positions in the Bamban-Zambales mountains, the author took the effort and checked with some available Japanese sources already cited, including that of the narratives of Col. Yasuji Okada, Kembu Shudan chief of staff.

All the local USAFFE guerrillas from south Tarlac (including Bamban and the Ayta mountain patrol), and northwest Pampanga participated in the campaign for the defeat of the Japanese Kembu composite division starting in January 23, 1945 until the year’s end. Official records of Philippine guerrillas available on-line at the PVAO’s Philippine Archives Collection all cited the heroic combat operations of the Filipino and Ayta Negrito guerrillas. Several published books, mostly authored by American historians like those related Major Henry Clay Conner of Squadron 155 (On A Mountainside, Resolve), and those related to the American guerrillas in Central Luzon (Schaefer’s Bataan Diary, Decker’s from Bataan to Safety) are good source of references that cited the activities of the local Filipino guerillas and the Ayta mountain patrol.

However, there are also Japanese materials or sources that provide some highlights on the role of the Filipino local guerrillas in the Bamban-Stotsenburg area. Col. Yasuji Okada’s official report, being the chief-of-staff of the Kembu Shudan, sum-up with the following:

“The situation (in May 1945) was bad at the beginning of this period but worsened steadily with the continued guerrilla pressure, the lack of shelter during this rainy season, and the difficulty of obtaining food.”

In my years of Japanese Study of WWII in Bamban-Stotsenburg area, one particular important papers were that of a war diary of Capt. Sadao Hachisu, Takayama Shitai, Kembu Group. Capt. Hachisu was originally posted on the mountain position overlooking the town of Bamban, retreated back near the Bamban-O’Donnell mountains with the collapsed of the Takayama Shitai by end of January 1945. His unit, detached from the Kembu Group main position due to the American ground and air attacks from Bamban, lost communication and retreated northward in the direction of the Tarlac River, into Moriones and in the Ayta Negrito ancestral lands of Surla and Iba further north. He was one of the very few survivors from Takayama and wrote a diary of his combat narratives during the whole period. Capt. Hachisu views of the Aytas as extracted on is war diary, as follows:

“Sniped by Negrito tribe, soldiers were shot from neck through shoulder, and killed instantly. Looking up, we found Negritoes swiftly moved and vanished from rock shadow of cliff, like monkeys. We recognized that even local residents living (Negritoes) deep in the mountains has hostile feeling against us, and started to hamper our operation. I was very depressed by foreseeing difficulty of operation in the future.”

DEATH OF ADMIRAL SUGIMOTO

There were also cases that the use of Japanese sources in search of materials for the Filipino combat operation can be of positive results. In spite of the fact that there is numerous unit history of the Filipino guerrillas, particularly those under the USAFFE command connected with General MacArthur Headquarters especially in 1945, a cross reference on the Japanese sources, particularly memoirs or diaries of survivors of Kembu Group written during the war and published post-war are of particular importance to historians and researchers. One instance is the Akamatsu Diary, written by Lieutenant Shinjo Akamatsu who used to be with the headquarters staff of the 341 “Shishi” Air Group. He kept a detailed account of his war experience from the time he landed at Margot Airfield (one of satellite air strips of Clark Field) in December 1944 until the mobilization of his unit consisting of aircrews and maintenance personnel into provisionary infantry of Kembu Group’s Naval Combat Sectors in Bamban Hills in January 1945 and the decimation of his unit at the war’s end in September. In his book, he cited an important piece of historical account related to the Filipino guerrillas; the killing of the leader of the Clark Defense Naval Forces of the Kembu Group; Vice-Admiral Ushie Sugimoto, by Filipino guerrillas on June 10, 1945 near the beach of Masinloc, Zambales as he tried to escape to Japan via submarine.

THE DESTRUCTION OF THE KEMBU COMPOSITE DIVISION

The defense of Clark Field begun in October 1944, at the start of the defense of the Philippines known to the Japanese as Shogo Operation (Victory, Leyte Operation) but more appropriately, Sho-1 Operation. It was also the beginning of a new kind of warfare, a suicide mission known to the Japanese as Special Attack or Tokubetsu Kogekitai. With the defeat of the Japanese air forces in late December 1944, it was inevitable that the next campaign will be on ground operations. There was massive military build-up of Clark Field, but the more important positions were of the mountainous areas of Bamban Hills. After the American landing at Lingayen, General Yamashita ordered the mobilization and occupation of the Bamban-Stotsenburg areas, designating the command as Kembu Group with mission to hamper the use of the airfields of Clark by the American forces through combat interdictions from mountain positions at Bamban Hills-Zambales mountains.

The northern anchor of Kembu Group was located on the Bamban Hills overlooking the main highway and the town, defended by Takayama Shitai but was crushed by the combined infantry, tank and artillery of the 40th Division US Army from January 23, 1945 and crushed on the month’s end. Clark Field was defended fanatically by Eguchi Detachment, mostly airfield battalions and aircrews on the same period and was captured by the 37th Division on January 30, 1945. In the first phase of the American attack on Kembu’s first line, about 5,000 troops were killed. The Takayama and Eguchi retreated to their prepared defense line westward of original positions for the battle on the main line. The Takaya Shitai occupied the second line, with main position at Storm King Mountain (Monikayo-Lagare Mountain), defended by airborne paratroops.

Along with the remnants of Takayama and Eguchi Detachment holed in their second line, the American 40th Division had broken the main line of Kembu Shudan after heavy fighting until late February 1945, with another 5,000 casualties. The survivors of the Kembu Group, still formidable at around 20,000 men, regrouped in the deeper fastness of the Zambales and Bamban mountains, at the last stand known as the Naval Combat Sector, where American 43rd and later 38th Division conducted combat and clearing operations until early April 1945. With the collapsed of the Kembu last stand sectors, the composite division was destroyed. To be able to survived, General Tsukada ordered the disbandment of the Kembu Shudan on April 6, 1945 and to compose smaller independent units for guerrilla actions and retreated on escape routes west into Mt. Pinatubo while other units retreated to the north in the direction of Tarlac.

IN PURSUIT OF GENERAL TSUKADA, ADMIRALS KONDO AND SUGIMOTO

With the American 38th and later the 6th Division in pursuit of the remnants of the Kembu Group in the far reaches of the Zambales mountains, the US Army’s special unit, the Alamo Scouts, along with Filipino guerrillas, conducted search operation for the capture of General Tsukada and Vice-Admiral Kondo Kazumae from March 28 to May 7, 1945 and investigate the intricate mountain trails usually used by the local Ayta Negritoes for reconnaissance. On June 10, 1945, local Filipino guerrillas operating in Iba and Masinloc killed Vice-Admiral Ushie Sugimoto in an encounter on the slope of the hill. Sugimoto and his staff from the Clark Defense Naval Forces Headquarters were actually waiting to be rescued by Japanese submarines for transfer back to Japan but were intercepted by Filipino guerrillas. Most of the Kembu survivors retreated to Mt. Pinatubo, where the headquarters was established. By August 1945, the situation for the Kembu survivors got worst, mainly for the lack of food and many men starved to death. With hunger, sickness, and misery, thousands of the Kembu survivors died on these mountains, in the valleys and on the edge of the rivers; the area became open graves.

SURRENDER & PRISONERS OF WAR

The announcement of Japan’s unconditional surrender was made on August 15, 1945. On August 24, the first news of the surrender of Japan was received by the 16th Naval Combat Sector holed on the western area of Mt. Pinatubo when American aircrafts dropped surrender cards. With the collapse of the communication system, the Eguchi Detachment, also holed near Pinatubo, sent messenger to Clark Field to confirm the surrender. The Kembu Group lost communication with the 14th Area Army north of Baguio. A messenger was sent from Kembu Shudan from Clark Field to locate the 14th Area Army for the instruction of the surrender.

On September 4, the Area Army ordered the decommissioning of the Japanese composite division of the Bamban-Stotsenburg area. Since majority of the survivors were suffering from hunger, sickness and malnutrition, American aircraft begun dropping medical supplies, food and clothing on designated areas of Mt. Pinatubo vicinity. Gaining strength, the defeated ghost soldiers of the once mighty Imperial Japanese forces marched to Clark Field on September 10, 1945 and caused the surrender. The 1,500 survivors of the Kembu Shudan “marched” to Manila and further south to Canlubang, Laguna on September 14 as the vanquished prisoners of war (POW), moved into the Prison Camp No. 1. Offices and men of the Kembu Group, much like the other commands of General Yamashita, tasted the paramount sufferings in the battle, sickness and hunger, until finally, only the few survivors can speak of the terrible defeat of the once proud Japanese soldiers.

The extracts of Capt. Sadao Hachisu war diary, one of the very few survivors from Bamban’s Takayama Shitai, expresses his view of the aftermath of his sojourn in the Bamban-Tarlac mountains:

“I sincerely hope that this description will inform reality of cruel defeat to younger generations, and warn them that they will never ever start abominable war again.”

Rhonie Dela Cruz

Bamban Historical Society

Bamban Museum of History

September 3, 2022

CITATION:

(1) Okada, Yasuji (Colonel, Chief of Staff of the Japanese Kembu Group). Japanese Monograph No. 9. “Outline of the Kembu Group Operation – Clark Sector, Record of the Philippine Operations Record of the Philippine Operation Vol. III Part 3”. First Demobilization Bureau, November 1946.

(2) Study of Japanese Operations on Luzon “Colonel Yasuji Okada – Narratives of Operations in Luzon Based”. File No. 8-5, Account No. 786/2-13 Special Staff US Army Historical Division 10th Information and Historical Service HQ, 8th Army. National Archives, College Park, Maryland. Bamban Historical Society Collection, Bamban Museum.

(3) Fuller, Richard. Shokan, Hirohito’s Samurai. London: Arms and Armour, 1992.

(4) Akamatsu, Shinjo. Diary of the Last Man Standing – An Epitaph for the 42,000 Japanese Killed in Clark Area. translated by Hitoshi Arai/Mike Fukuda. Tokyo, Japan: Kojinsha, 1973.

(5) Hachiso, Sadao. War Diary of Captain Sadao Hachiso 1945. Manuscript original in Japanese. Translated by Ed Saito. Bamban Historical Society Collection, Bamban Museum, Bamban, Tarlac.

PHOTOS

(a) Japanese Kembu survivors and prisoners of war (POW), after surrender in September 1945. The last survivors of the Kembu Group had made escape and retreat, in the Pinatubo area, and some to the north in western Tarlac.

Shinjo Akamatsu, Diary of the Last Man Standing, Bamban Museum Collection. 1

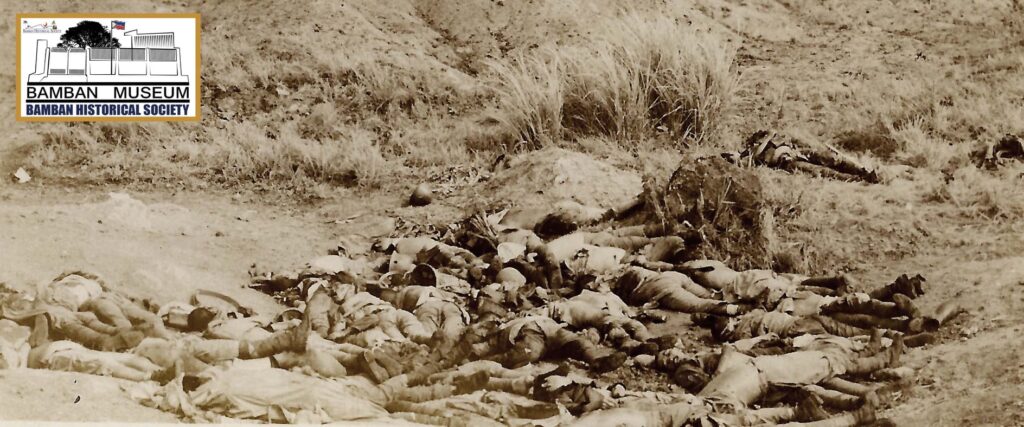

(b) Japanese war dead, on the promontory of Matsuyama, Bamban Hills, in the aftermath of banzai attack on American 160th Infantry position in February 1945.

40th Division Photo, Courtesy of Karon Thomas, Bamban Museum Collection. 2

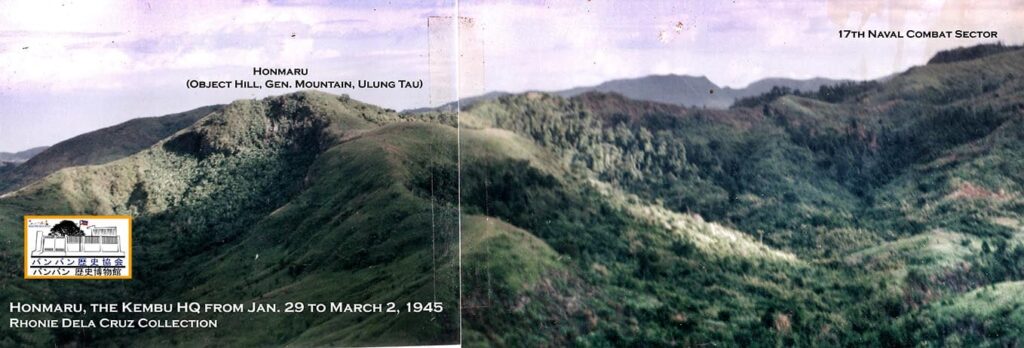

(c) Photo of Honmaru (General Mountain), part of Bamban Hills as Kembu Group HQ and the headquarters of Clark Defense Force under Admiral Sugimoto in late January and February 1945. The 160th Infantry, 40th Division US Army made the toughest fights at Honmaru, where the unit received the Presidential Citation award.

Rhonie Dela Cruz/BHS Photo. 3

(d) A M7 105 mm Howitzer Motor Carriage named “Super Rabbit” attached to the Cannon Company of the 160th Infantry, 40th Division US Army conducts fire support on the infantry attack on Snake Hill West, Bamban Hills in February 1945 against Japanese positions holed on the tunnels.

40th Division Photo, courtesy of Karon Thomas.

(e) Japanese war dead in the battlefield and piled in decomposition state, circa 1945.

38th Division Photo, provided by the late Marshall Skiff (151st Infantry). Bamban Museum Collection.

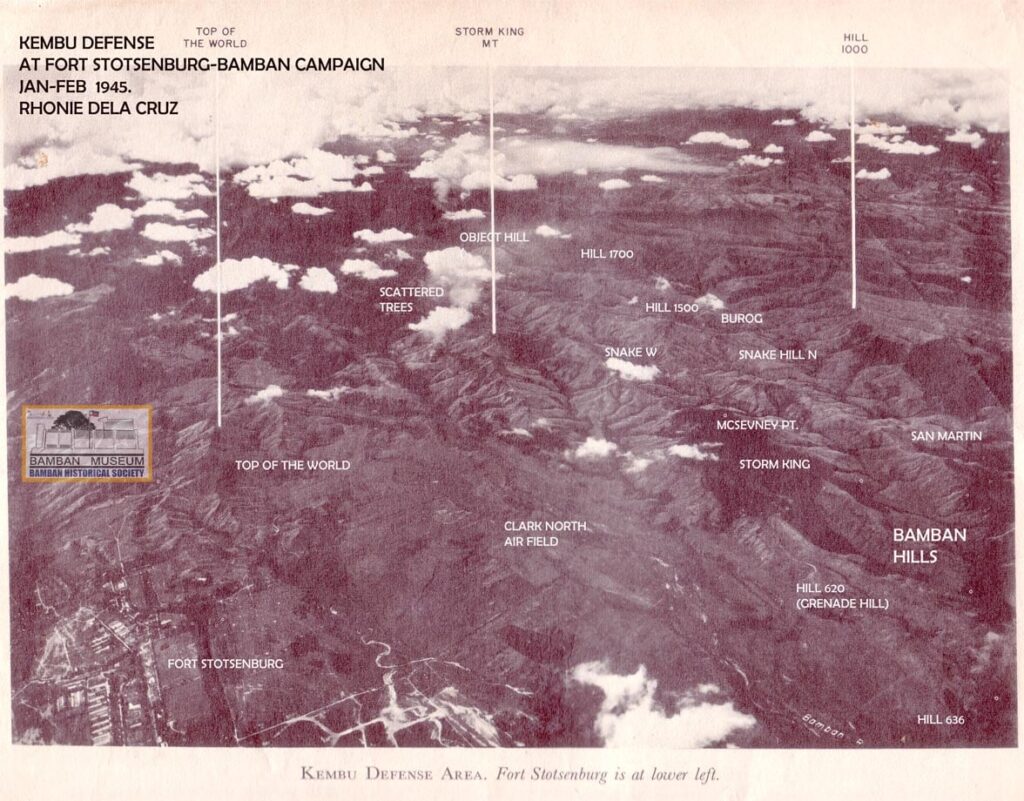

(f) Aerial view of the depth of Bamban-Stotsenburg area of the Kembu Group, circa 1945.

Source: US Army in WWII, Triumph in the Philippines.

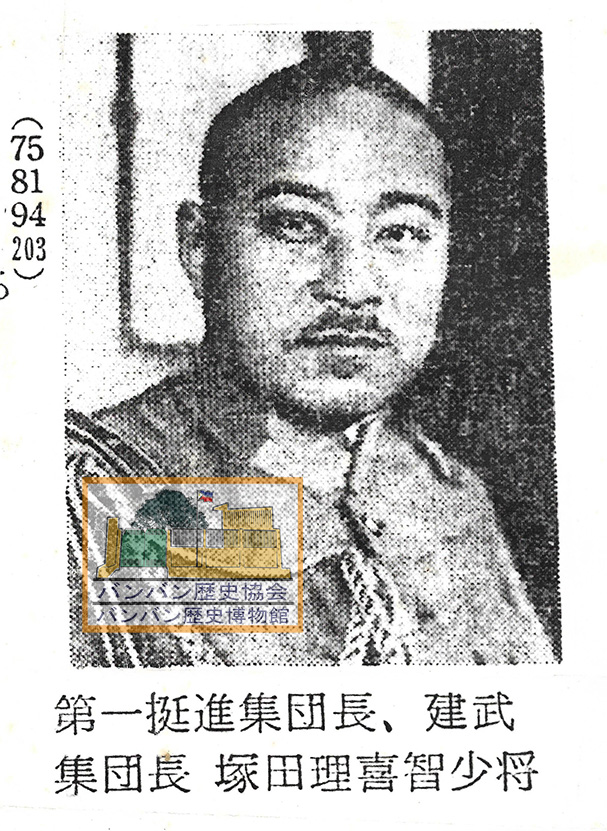

(g) Lieutenant-General Rikichi Tsukada, commander of the Japanese Kembu Group.

Source: Records of the Kembu Group (original in Japanese). Institute for National Defense Studies, Tokyo, Japan. Bamban Museum Collection.

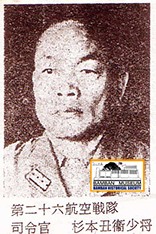

(h) Vice-Admiral Ushie Sugimoto, commander of Clark Naval Defense Force – Kembu Shudan. He was killed by Filipino guerrillas near Iba on June 10, 1945.

Source: Records of the Kembu Group (original in Japanese). Institute for National Defense Studies, Tokyo, Japan. Bamban Museum Collection.

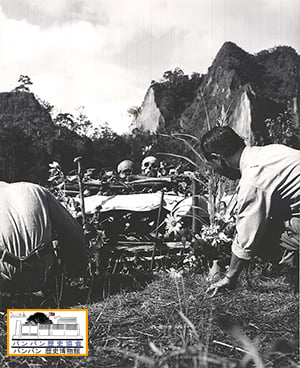

(i) In this photo, Takanori Yanagimoto, former commanding officer of the Yanagimoto Shitai, on a special mission to collect the remains of Japanese war-dead in the Bamban-Clark area, circa 1950s.

Photo from American Collection, Ateneo de Manila University

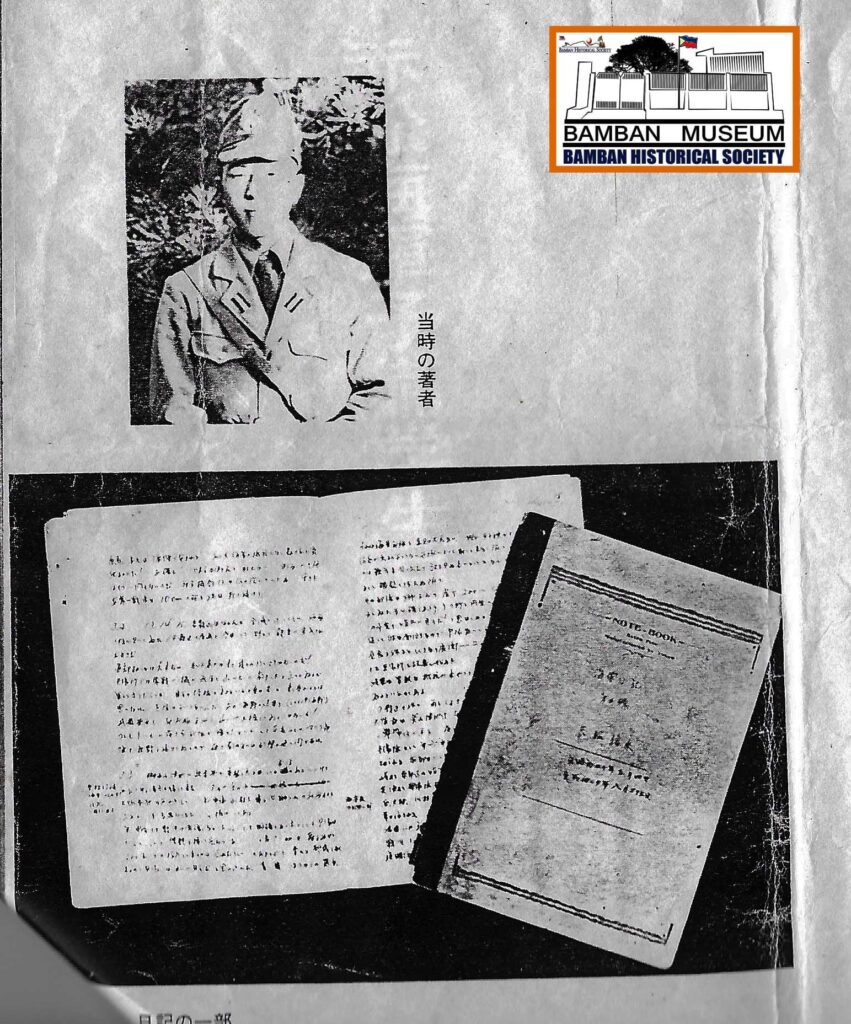

(j) Japanese sources, like this from Lieutenant Shinjo Akamatsu war diary, as important materials in the Japanese WWII Study in Bamban-Clark area.

Source: Shinjo Akamatsu, BHS Center for Japanese WWII Study, Bamban Museum

(k) Facsimile of Captain Hachisu Sadao war diary, formerly of the Takayama Shitai, Kembu Group.

Source: Shinjo Akamatsu, BHS Center for Japanese WWII Study, Bamban Museum